A Volcanic Eruption That Reverberates 200 Years Later

In April 1815, the most powerful volcanic blast in recorded history shook the planet in a catastrophe so vast that 200 years later, investigators are still struggling to grasp its repercussions. It played a role, they now understand, in icy weather, agricultural collapse and global pandemics — and even gave rise to celebrated monsters.

Around the lush isles of the Dutch East Indies — modern-day Indonesia — the eruption of Mount Tambora killed tens of thousands of people. They were burned alive or killed by flying rocks, or they died later of starvation because the heavy ash smothered crops.

More surprising, investigators have found that the giant cloud of minuscule particles spread around the globe, blocked sunlight and produced three years of planetary cooling. In June 1816, a blizzard pummeled upstate New York. That July and August, killer frosts in New England ravaged farms. Hailstones pounded London all summer.

A recent history of the disaster, “Tambora: The Eruption that Changed the World,” by Gillen D’Arcy Wood, shows planetary effects so extreme that many nations and communities sustained waves of famine, disease, civil unrest and economic decline. Crops failed globally.

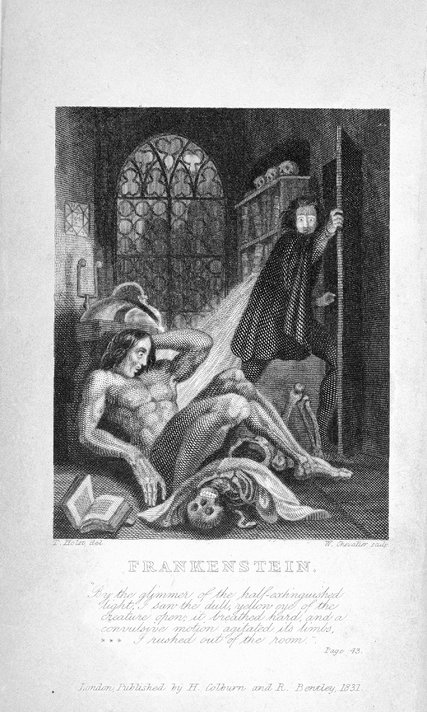

“The year without a summer,” as 1816 came to be known, gave birth not only to paintings of fiery sunsets and tempestuous skies but two genres of gothic fiction. The freakish progeny were Frankenstein and the human vampire, which have loomed large in art and literature ever since.

“The paper trail,” said Dr. Wood, a University of Illinois professor of English, “goes back again and again to Tambora.”

The gargantuan blast — 100 times bigger than Mount St. Helens’s — and its ensuing worldwide pall have been the subject of increasing study over the years as scientists have sought to comprehend not only the planet’s climatological past but the future likelihood of such global disasters.

Clive Oppenheimer, a volcanologist at the University of Cambridge, who has studied the Tambora catastrophe, put the chance of a similar explosion in the next half-century as relatively low — perhaps 10 percent. But the consequences, he added, could run extraordinarily high.

“The modern world,” Dr. Oppenheimer said, “is far from immune to the potentially catastrophic impacts.”

Before it exploded, Tambora was the tallest peak in a land of cloudy summits. It lay atop the tropic isle of Sumbawa, its spires rising nearly three miles. Long dormant, the mountain was considered a home to gods. Villages dotted its slopes, and nearby farmers grew rice, coffee and pepper.

On the evening of April 5, 1815, according to contemporary accounts, flames shot from its summit and the earth rumbled for hours. The volcano then fell silent.

Five days later, the peak exploded in a deafening roar of fire, rock and boiling ash that was heard hundreds of miles away. Flaming rivers of molten rock ran down the slopes, destroying tropic forests and villages. Days later, still raging but by then hollow, the mountain collapsed, its height suddenly diminished by a mile.

Locally, an estimated 100,000 people died. Sumbawa never recovered.

The repercussions were global, but no one realized that the widespread death and mayhem arose from an eruption halfway around the world. What emerged was regional folklore. New Englanders called 1816 “eighteen hundred and froze to death.” Germans called 1817 the year of the beggar. These and many other local episodes remained unknown or unconnected.

It was scientists who began to stitch together the big picture, especially the peculiar link between fiery volcanism and icy weather. An overarching goal was to separate natural climate fluctuations from those of human origin. One after another, studies came back to New England and its frigid summer of 1816.

Dr. Wood expanded the portrait in his book, which is due out in paperback next month. It draws on hundreds of scientific papers as well as Dr. Wood’s knowledge of 19th-century literature to lay bare three years of planetary mayhem as well as the origins of fictional demons.

“My interest was to understand a global event,” Dr. Wood said in an interview, “and that meant serious detective work in lots of unfamiliar archives.” Five years of inquiry took him to China, Europe and India.

It also transported him to Tambora, where he braved leeches and razor-sharp leaves to peer across its yawning caldera, four miles from rim to rim.

The exploding mountain, the book notes, heaved some 12 cubic miles of earthen matter to a height of more than 25 miles. While coarse particles soon rained out, finer ones traveled the high winds in a spreading cloud. “It passed,” Dr. Wood wrote, “across both south and north poles, leaving a telltale sulfate imprint on the ice for paleoclimatologists to discover more than a century and a half later.”

The global veil, high above rain clouds, reflected much sunlight back into space. So the planet cooled. The pall, Dr. Wood said, also spawned tempests far below.

His book reprints an 1816 oil painting of Weymouth Bay, a sheltered cove on England’s south coast, by John Constable — the sky above churning with dark clouds. “Everywhere,” Dr. Wood said, “the volcanic winds blew hard.” He noted that both history and computer models speak of fierce storms back then.

The particles high in the atmosphere also produced spectacular sunsets, as detailed in the famous paintings of J.M.W. Turner, the English landscape pioneer. His vivid red skies, Dr. Wood remarked, “seem like an advertisement for the future of art.”

The story also comes alive in local dramas, none more important for literary history than the birth of Frankenstein’s monster and the human vampire. That happened on Lake Geneva in Switzerland, where some of the most famous names of English poetry had gone on a summer holiday.

By 1816, Switzerland, landlocked and famously rugged, was beginning to reel from the bad weather and failed crops. Starving mobs stormed bakeries after bread prices soared. The book recounts a priest’s distress: “It is terrifying to see these walking skeletons devour the most repulsive foods with such avidity.”

That June, the cold and stormy weather sent the English tourists inside a lakeside villa to warm themselves by a fire and exchange ghost stories. Mary Shelley, then 18, was part of a literary coterie that included Percy Shelley, her future husband, as well as Lord Byron. Wine flowed, as did laudanum, a form of opium. Candles flickered.

In this moody atmosphere, Mary Shelley came up with her lurid tale of Frankenstein, which she published two years later. And Lord Byron hit on the outline of the modern vampire tale, published later by a compatriot as “The Vampyre.” The freakish weather also inspired Byron’s apocalyptic poem “Darkness.”

Dr. Wood’s book documents many other repercussions of the planetary chill, devoting a chapter to a cholera pandemic of 1817 that began in India and globally killed tens of millions of people. Dr. Wood attributes its rise to a deadly combination of monsoonal changes and pounding rains — a main theory of leading cholera detectives.

The pandemic spread and eventually reached the Dutch East Indies. On Java alone it killed an estimated 125,000 people — more, Dr. Wood noted, “than died in the volcanic eruption itself.”

He also profiles the wintry chill in Yunnan Province in southern China, a land of mountains and jungles roamed by tigers and elephants. Rice crops there quickly failed, and famine gnawed deep for years. In July 1816, Dr. Wood noted, the province had “unprecedented snows.”

The poet, Li Yuyang, who was 32 as Tambora began its global rampage, wrote of cold downpours and flash flooding in “A Sigh for Autumn Rain.”

Water spilling from the eaves deafens me.

People rush from falling houses in their thousands

And tens of thousands, for the work of the rain

Is worse than the work of thieves. Bricks crack. Walls fall.

In an instant, the house is gone.

Dr. Wood closes with a portrait of the eastern United States in 1816, focusing first on upstate New York. One day that June, four young classmates walked to school, most barefoot. Then a blizzard struck. Dismissed early, the children ran for their lives as the snow rose to their knees. They succeeded in reaching warm cabins and fires.

For Thomas Jefferson, the pain lasted longer. The retired third president of the United States, at his estate in Virginia, faced a disastrous summer in 1816 because of the remarkably short growing season. The next year was just as bad.

In a letter, Jefferson expressed concern about the possible ruin of his Monticello farm “if the seasons should, against the course of nature hitherto observed, continue constantly hostile to our agriculture.”

The countless victims and occasional beneficiaries of Tambora’s fury were oblivious to the volcanic roots of their circumstances, Dr. Wood noted, making the challenge of writing about it formidable and “occasionally mind-bending.”

More generally, he said, the revelation of global volcanic ruin — a portrait 200 years in the making — offers a kind of meditation on the difficulty of uncovering the subtle effects of climate change, whether its origins lie in nature’s fury or the invisible byproducts of human civilization.

It is, Dr. Wood remarked, “hard to see and no less difficult to imagine.”

Because of an editing error, a picture caption on Tuesday with an article about the effects of the Mount Tambora eruption in 1815 misidentified the painter of a harbor scene depicting a vivid sky shadowed by ash clouds. He was Caspar David Friedrich, not David Caspar Friedrich.